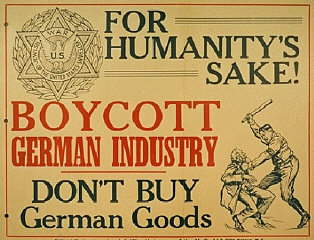

Poster (issued by the Jewish War Veterans of the United States) calling for a boycott of German goods. New York, United States, between 1937 and 1939.

— Jewish War Veterans Museum

During World War II, rescue of Jews and other victims of the Nazis was not a priority for the United States government. Nor was it always clear to Allied policy makers how they could pursue large-scale rescue actions behind German lines. Due in part to antisemitism (prejudice against or hatred of Jews), isolationism, the economic Depression, and xenophobia (prejudice against or fear of foreigners), the refugee policy of the U.S. State Department (led by Secretary of State Cordell Hull) made it difficult forrefugees to obtain entry visas to the United States.

The U.S. State Department also delayed publicizing reports of genocide. In August 1942, the State Department received a cable revealing Nazi plans for the murder of Europe's Jews. However, the report, sent by Gerhart Riegner (the World Jewish Congress [WJC] representative in Geneva) was not passed on to its intended recipient, American Jewish leader and WJC president Stephen Wise. The State Department asked Wise, who had almost simultaneously received the report via British channels, to refrain from announcing it.

The United States failed to act decisively to rescue victims of the Holocaust. On April 19, 1943, U.S. and British representatives met in Bermuda to find solutions to wartime refugee problems. No significant proposals emerged from the conference. In 1943, Polish underground courier Jan Karski informed President Franklin D. Roosevelt of reports of mass murder received from Jewish leaders in the Warsaw ghetto. U.S. authorities did not, however, initiate any action aimed at rescuing refugees until 1944, when Roosevelt established the War Refugee Board (WRB). That year the WRB set up the Fort Ontario Refugee Center in Oswego, NY, to facilitate rescue of imperiled refugees. By the time the War Refugee Board was established, however, four fifths of the Jews who would die in the Holocaust were already dead.

WHY AUSCHWITZ WAS NOT BOMBED

By the spring of 1944, the Allies knew of the killing operations using poison gas at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Between May 15 and July 9, 1944, a total of 437,402 Jews were deported from Hungary. Most were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On some days as many as 10,000 people were killed in its gas chambers. Well before the deportations from Hungary, the U.S. War Department had essentially ruled out using military personnel in rescue missions. It was argued that the most effective relief for Nazi victims was a swift end to the war.

By the spring of 1944, the Allies knew of the killing operations using poison gas at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Between May 15 and July 9, 1944, a total of 437,402 Jews were deported from Hungary. Most were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On some days as many as 10,000 people were killed in its gas chambers. Well before the deportations from Hungary, the U.S. War Department had essentially ruled out using military personnel in rescue missions. It was argued that the most effective relief for Nazi victims was a swift end to the war.

In desperation, Jewish organizations made various proposals to halt the extermination process and rescue Europe's remaining Jews. A few Jewish leaders called for the bombing of the Auschwitz gas chambers; others opposed it. Like some Allied officials, both sides feared the death toll or the German propaganda that might exploit any bombing of the camp's prisoners. No one was certain of the results.

In the summer and fall of 1944, the World Jewish Congress and the U.S. government's War Refugee Board forwarded requests to bomb Auschwitz to the U.S. War Department. These requests were denied. Yet within a week, the U.S. Army Air Force carried out a heavy bombing of the I.G. Farben synthetic oil and rubber (Buna) works near Auschwitz III-less than five miles from Auschwitz-Birkenau. The gas chambers remained untouched.

For prisoners at Auschwitz, the bombs dropping nearby gave hope. One survivor recalled: "We were no longer afraid of death; at any rate, not of that death. Every bomb that exploded filled us with joy and gave us new confidence in life." Proponents of the bombing continue to argue that such an action, while it might have killed prisoners, could have hampered the killing operations and perhaps ultimately saved lives. At the very least, they believe, it might have demonstrated Allied concern for the fate of the Jews.

Resources

Breitman, Richard, and Allen Kraut. American Refugee Policy and European Jewry, 1933-1945. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Feingold, Henry L. Bearing Witness: How America and Its Jews Responded to the Holocaust. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

Gurock, Jeffrey S., editor. America, American Jews, and the Holocaust. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Lipstadt, Deborah E. Beyond Belief: The American Press and the Coming of the Holocaust, 1933-1945. New York: Free Press, 1986.

Neufeld, Michael J., and Michael Berenbaum, editors. The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted It?New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000.

Wyman, David S. Paper Walls: America and the Refugee Crisis, 1938-1941. New York: Pantheon Books, 1985.

Wyman, David S. The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941-1945. New York: The New Press, 1998.

Related Articles:

An Overview of the Holocaust: Topics to Teach »

United States Policy and its Impact on European Jews »

Franklin Delano Roosevelt »

Moses Beckelman »

Henry Morgenthau »

United States Policy Toward Jewish Refugees, 1941-1952 »

U.S. Army units »

The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk »

The United States Army Signal Corps »

United States Policy and its Impact on European Jews »

Franklin Delano Roosevelt »

Moses Beckelman »

Henry Morgenthau »

United States Policy Toward Jewish Refugees, 1941-1952 »

U.S. Army units »

The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk »

The United States Army Signal Corps »

Related Links:

Related podcast: Stephen H. Norwood »

Related podcast: Laurel Leff »

America and the Age of Genocide: Committee on Conscience presentation »

Seeking Refuge in America Today: Committee on Conscience presentation »

USHMM Library Bibliography: The United States and the Holocaust »

Kristallnacht: How did religious leaders in the United States respond? »

Related podcast: Laurel Leff »

America and the Age of Genocide: Committee on Conscience presentation »

Seeking Refuge in America Today: Committee on Conscience presentation »

USHMM Library Bibliography: The United States and the Holocaust »

Kristallnacht: How did religious leaders in the United States respond? »