Would the creation of a Palestinian state by vote of the United Nations General Assembly, expected in September, be illegal?

Yes, according to a recent letter to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon. Signed by an array of lawyers, law professors and international law experts, it asks him to block the forthcoming resolution, promoted by the Palestinian Authority, for recognition of a Palestinian state within the 1949 Armistice lines.

The letter was drafted by lawyers affiliated with the Legal Forum for the Land of Israel, a non-profit organization founded in 2004 to find "fair and equitable solutions" for Israelis then about to be evacuated from Gaza.

Among its distinguished signers were Alan Baker, former legal adviser for the Israeli Foreign Ministry and ambassador to Canada, and Meir Rosenne, another former legal adviser for the Foreign Ministry and ambassador to the United States. They claim that UN recognition would be "contrary to international law, UN resolutions and existing agreements."

Their letter, in effect a legal brief, argues that such a resolution would contravene UN Security Council Resolutions adopted after the Six-Day and Yom Kippur wars. It would be "in stark violation" of existing agreements between Israel and the Palestinians.

Indeed, "the legal basis for the establishment of the State of Israel," they indicate, goes back to 1922 when the League of Nations affirmed "the establishment of a national home for the Jewish People in the historical area of the Land of Israel."

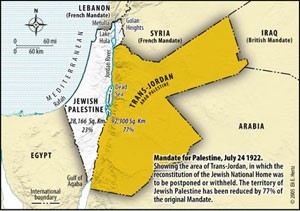

Empowered to enact international law for the new postwar world order, the League conferred on Great Britain a Mandate for Palestine. "Palestine" was defined as the land east and west of the Jordan River, now comprising Jordan, the West Bank and Israel.

But in what became the first partition of Palestine, now long forgotten or ignored (even by Israeli government officials), the British government lopped off all the land east of the Jordan River, three-quarters of the designated Mandatory territory, and bestowed it upon Abdullah, son of the Sharif of Mecca, for his own kingdom of Trans-Jordan.

The entire remainder, west of the Jordan to the Mediterranean, was redefined as "Palestine" and designated for the "Jewish National Home," a phrase borrowed from Lord Balfour's famous letter of November 2, 1917. But the League went beyond that vague and indeterminate assurance. Article 6 of the Palestine Mandate explicitly protected "close settlement by Jews" in the shrunken land to be called Palestine.

That guarantee remains the international legal foundation for Jewish settlements built ever since the Six-Day War returned Israel to its ancient Jewish homeland. It has never been rescinded.

As signers of the Legal Forum letter indicate, any General Assembly attempt to create a Palestinian state in that territory would violate an array of international guarantees. Among them, most crucially, is Article 80 of the UN Charter. It explicitly protected the rights of "any peoples or the terms of existing international instruments to which members of the United Nations may respectively be parties."

Drafted by Jewish representatives (including Prime Minister Netanyahu's father), Article 80 became known as "the Palestine clause." It preserved, under international law, the rights of the Jewish people to "close settlement" in all the land west of the Jordan River, even after the British Mandate had expired and the League of Nations had ceased to exist.

Those rights were flagrantly violated when Jordan invaded the fledgling Jewish state and claimed sovereignty over the West Bank in 1949. But the Jordanian claim had no standing in international law and was never recognized.

After the Six-Day War, Security Council Resolution 242 permitted Israel to administer the West Bank until "a just and lasting peace in the Middle East" was achieved. That, of course, has not yet happened.

Even then, however, Israel would only be required to withdraw its armed forces "from territories" - not from "the territories" or "all the territories" (proposals that were defeated in both the Security Council and the General Assembly).

The absence of "the" - the now famous missing definite article - was neither an accident nor an afterthought.

It resulted from what Yale Law School Professor Eugene W. Rostow, then undersecretary of state for political affairs, described as more than five months of "vehement public diplomacy" to decisively clarify the meaning of Resolution 242.

No prohibition - or even limitation - on Jewish settlement, guaranteed west of the Jordan River under the League of Nations Mandate forty-five years earlier, was adopted.

As the Legal Forum letter indicates, "1967 borders" (so labeled recently by President Obama) "do not exist, and have never existed." Under the terms of the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and the invading Arab states, the newly established "Armistice Demarcation Lines" were "without prejudice to future territorial settlements or boundary lines."

Therefore, the letter signers conclude, those borders "cannot be accepted or declared to be the international boundaries of a Palestinian state."

Should the UN General Assembly approve the current Palestinian proposal, the Palestinians would also be in "fundamental breach" of the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Accord, when the signatories agreed not to attempt to change the status of contested territory before permanent status negotiations were concluded - certainly not before they were even begun.

* * * * *

After the Six-Day War the core Zionist commitment to settling the land of Israel, which had driven state-building efforts since the 1880s, passed from secular to religious Israelis. That transformation surely explains why successive Israeli governments, whether led by Labor or Likud, have either maintained silence - or demonstrated intense hostility - toward Zionist settlers wearing kippot or long skirts.

At best ambivalent - and usually hostile - toward Jews in Judea and Samaria, government officials have resolutely maintained silence about the international guarantees for the "close settlement" of Jews west of the Jordan River.

Joined by a chorus of academic intellectuals, journalists, and cultural luminaries, they have been exceedingly leery of strengthening religious Zionism by authorizing new settlements or enlarging existing ones. The special venom toward settlers displayed by current Defense Minister (and former prime minister) Ehud Barak expresses the deep-rooted hostility of Labor Party and left-wing Zionists toward their despised ideological challengers.

Not all settlers, to be sure, are religious. The majority doubtlessly chose to live in Judea and Samaria because housing prices were lower, and the quality of life better, in their sparkling new communities than where they previously lived.

Perhaps one hundred thousand settlers are religious Zionists who claim the land as Israel's biblical birthright and inheritance. Unlike Tel Avivians, who gaze across the Mediterranean to Los Angeles and the Silicon Valley for their sources of cultural inspiration, these Israelis stand on the bedrock of Jewish history, looking to the past and to sacred texts, not to the West, for inspiration.

Critics from the secular left have been unrelenting in their castigation of settlements. In Lords of the Land (2007), the first comprehensive history of the settlement movement, historian Idith Zertal and Haaretz journalist Akiva Eldar lacerated settlers for their illegal occupation of "Palestinian" land. The "malignancy of occupation," they wrote, "in contravention of international law," has "brought Israel's democracy to the brink of an abyss."

But persistent efforts to undermine the legitimacy of Israeli settlements, wrote international legal expert Julius Stone thirty years ago, have been nothing less than a "subversion of basic international law principles." They still are. Yet the United Nations, with an international constituency that has been relentlessly hostile to Israel ever since it first hallucinated that "Zionism is racism" in 1975, keeps trying.

Catering to international support for Palestinian victimization claims, the International Criminal Court, established by the UN General Assembly in 1998, made Jewish settlement a "war crime." But Israel (like the United States) "unsigned" from the statute of authorization for the Court; furthermore, as international legal scholar Jeremy Rabkin indicates, the Court lacks jurisdiction over "crimes" committed before 2002. By then, virtually all the currently existing Jewish settlements had already been established. That renders any designation of settlements as "war crimes" meaningless ex post facto rhetoric - although not without power to elicit ever more anti-Israel venom.

The question never asked is whether a Palestinian state in the land reserved under international law for "close settlement" by Jews is even legal. The Jewish claim, forged by three thousand years of history in the Land of Israel, including two eras of national sovereignty, reinforced in the modern era by a succession of international legal guarantees, is indisputable.

The Palestinian claim, by contrast, is a contrived recent invention. Palestinians, as Barbara Lerner has written (National Review Online, June 17), "are not a people distinguishable by virtue of their common genes and/or language, religion, culture, history, or form of government."

Devised by Arabs who only recently identified themselves as "Palestinians," it is built on the foundation of perpetual victimization claims, the international determination to delegitimize Israel, and - perhaps most revealing - the pillaging of Jewish and Zionist history.

"Palestine" was so named by the Romans after they crushed the Bar Kochba rebellion in 133 CE. Any ancestors of present-day Palestinians who may have lived in Palestine under Ottoman or British rule were considered by others, and by themselves, to be Arabs. In 1948, without undue protest, they became Jordanians.

Not until the creation of the PLO by Arab states at the Arab League Summit (1964) did they become "Palestinians." It took another decade, which included the stunning victory of Israel in the Six-Day War, before statehood was mentioned on the Palestinian wish list.

The validity of the Palestinian historical claim can be measured by its sources - nearly all of which, revealingly, are Jewish. In a remarkable inversion, a people without an identifiable national identity or history until well into the 20th century has plundered Zionist history to create its own illusory past in a land that was never theirs.

Relying on the Hebrew Bible, Palestinians (like Arabs throughout the Middle East) claim Ishmael, Abraham's son by his servant Hagar, as their founding ancestor. They adopted as their ancient forebears the Canaanites, who, according to the biblical narrative, were displaced by conquering Israelites. (Palestinian history not only invents itself; it anticipates itself.)

Insisting that Jews never had national commonwealths in the Land of Israel many centuries before the birth of Islam, Palestinians reject irrefutable historical and archeological evidence to the contrary.

So, too - like Muslims throughout the Middle East - they resolutely deny that there ever was a Temple in Jerusalem and that the Western Wall has been a Jewish holy site ever since its destruction in 70 CE. Yet triumphant Islam built the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aksa mosque on the Temple Mount precisely because it had been sacred Jewish space.

In Hebron, similarly, Muslim conquerors seized the Cave of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs where Jews had already worshipped at the graves of their biblical ancestors for more than ten centuries. Transforming it into a mosque, Muslims barred Jewish "infidels" from entry for seven hundred years - until the Six-Day War forced open the doors.

Even the flotillas to Gaza, beginning with the notorious Mavi Marmara a year ago, are modeled after the rickety refugee ships that tried to bring desperate Jews, fleeing from Nazi terror and extermination, to Palestine before and after World War II. The most famous of these was the Exodus, with thousands of Holocaust survivors on board, turned away by the British government in 1947. Any resemblance is, of course, purely intentional - and patently absurd.

* * * * *

Might there be an alternative to Palestinian usurpation of the ancient Jewish homeland? Certainly West Bank Palestinians must be guaranteed the right to remain in place, living in their cities and villages and farming their land. They should have the option of citizenship in the Kingdom of Jordan, occupying two-thirds of Mandatory Palestine, where more than half the population is already Palestinian. The distances are not far: from Nablus (biblical Shechem, where Jacob dwelled), the second largest Palestinian city, to Amman it's only 68 miles.

King Abdullah might prefer not to have an even more menacing democratic challenge to his Hashemite minority rule, but that would be a small price to pay for peace.

Jewish settlements, and other land legally owned by Jews in Judea and Samaria, would become part of the Jewish state. On Israeli land there would be no distinctive restrictions on development. A joint Israeli-Palestinian police force could continue to patrol the land between Palestinian and Jewish communities, as has now been done for nearly twenty years.

In Hebron, where the special challenge of a divided city exists, Jews would be free to inhabit Jewish-owned property, which they often cannot (by edict of their own government), and to purchase land and buildings from willing Arab sellers. A continuing Israeli military presence in the Jewish zone of the city, where Arabs also live, would be required indefinitely for the safety of Jewish residents.

In May 1967, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook memorably cried out to his graduates, assembled at the Mercaz HaRav yeshiva in Jerusalem to celebrate Independence Day: "They have divided my land. Where is our Hebron? Have we forgotten it? And where is Shechem? And our Jericho - will we forget them?"

One month later, at the Western Wall, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan promised the victorious nation: "We have returned to all that is holy in our land. We have returned never to be parted from it again."

President Obama, of course, demands otherwise. But his insistence on the 1949 Armistice lines as the framework for negotiation, his determination to propel Palestinian statehood by the end of this year, and his silence on the Palestinian "right of return" (to Israel) easily qualify him as the president most hostile to the Jewish state since 1948 (with the possible exception of Jimmy Carter).

Having quickly turned against a longtime American ally in Egypt, then "leading from behind" in Libya, and now remaining silent while the Assad regime slaughters innocent Syrian civilians, Obama focuses relentlessly on Israel as the primary source of Middle East problems.

The return of Jews to the Land of Israel is what Zionism has always been about. A Palestinian state in the Jewish homeland will undermine it from within.

To find other articles in Think-Israel that address the topic that Mandated Palestine is in an irrevocable trust for the Jewish people, find articles by Shifftan, Grief, Brand, Belman, Kaplan. Other key words are "mandated palestine" and "irrevocable trust". Also see the video entitled "San Remo's Mandate: Israel's 'Magna Carta'" here and a discussion by Jacques Gauthier on the 1967 Lines here.

Jerold S. Auerbach is the author of "Brothers at War: Israel and the Tragedy of the Altalena," published in May by Quid Pro Books. This article was published June 29, 2011 in the Jewish Press and is archived at

http://www.jewishpress.com/pageroute.do/48830/

Yes, according to a recent letter to UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon. Signed by an array of lawyers, law professors and international law experts, it asks him to block the forthcoming resolution, promoted by the Palestinian Authority, for recognition of a Palestinian state within the 1949 Armistice lines.

The letter was drafted by lawyers affiliated with the Legal Forum for the Land of Israel, a non-profit organization founded in 2004 to find "fair and equitable solutions" for Israelis then about to be evacuated from Gaza.

Among its distinguished signers were Alan Baker, former legal adviser for the Israeli Foreign Ministry and ambassador to Canada, and Meir Rosenne, another former legal adviser for the Foreign Ministry and ambassador to the United States. They claim that UN recognition would be "contrary to international law, UN resolutions and existing agreements."

Their letter, in effect a legal brief, argues that such a resolution would contravene UN Security Council Resolutions adopted after the Six-Day and Yom Kippur wars. It would be "in stark violation" of existing agreements between Israel and the Palestinians.

Indeed, "the legal basis for the establishment of the State of Israel," they indicate, goes back to 1922 when the League of Nations affirmed "the establishment of a national home for the Jewish People in the historical area of the Land of Israel."

Empowered to enact international law for the new postwar world order, the League conferred on Great Britain a Mandate for Palestine. "Palestine" was defined as the land east and west of the Jordan River, now comprising Jordan, the West Bank and Israel.

But in what became the first partition of Palestine, now long forgotten or ignored (even by Israeli government officials), the British government lopped off all the land east of the Jordan River, three-quarters of the designated Mandatory territory, and bestowed it upon Abdullah, son of the Sharif of Mecca, for his own kingdom of Trans-Jordan.

The entire remainder, west of the Jordan to the Mediterranean, was redefined as "Palestine" and designated for the "Jewish National Home," a phrase borrowed from Lord Balfour's famous letter of November 2, 1917. But the League went beyond that vague and indeterminate assurance. Article 6 of the Palestine Mandate explicitly protected "close settlement by Jews" in the shrunken land to be called Palestine.

That guarantee remains the international legal foundation for Jewish settlements built ever since the Six-Day War returned Israel to its ancient Jewish homeland. It has never been rescinded.

As signers of the Legal Forum letter indicate, any General Assembly attempt to create a Palestinian state in that territory would violate an array of international guarantees. Among them, most crucially, is Article 80 of the UN Charter. It explicitly protected the rights of "any peoples or the terms of existing international instruments to which members of the United Nations may respectively be parties."

Drafted by Jewish representatives (including Prime Minister Netanyahu's father), Article 80 became known as "the Palestine clause." It preserved, under international law, the rights of the Jewish people to "close settlement" in all the land west of the Jordan River, even after the British Mandate had expired and the League of Nations had ceased to exist.

Those rights were flagrantly violated when Jordan invaded the fledgling Jewish state and claimed sovereignty over the West Bank in 1949. But the Jordanian claim had no standing in international law and was never recognized.

After the Six-Day War, Security Council Resolution 242 permitted Israel to administer the West Bank until "a just and lasting peace in the Middle East" was achieved. That, of course, has not yet happened.

Even then, however, Israel would only be required to withdraw its armed forces "from territories" - not from "the territories" or "all the territories" (proposals that were defeated in both the Security Council and the General Assembly).

The absence of "the" - the now famous missing definite article - was neither an accident nor an afterthought.

It resulted from what Yale Law School Professor Eugene W. Rostow, then undersecretary of state for political affairs, described as more than five months of "vehement public diplomacy" to decisively clarify the meaning of Resolution 242.

No prohibition - or even limitation - on Jewish settlement, guaranteed west of the Jordan River under the League of Nations Mandate forty-five years earlier, was adopted.

As the Legal Forum letter indicates, "1967 borders" (so labeled recently by President Obama) "do not exist, and have never existed." Under the terms of the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and the invading Arab states, the newly established "Armistice Demarcation Lines" were "without prejudice to future territorial settlements or boundary lines."

Therefore, the letter signers conclude, those borders "cannot be accepted or declared to be the international boundaries of a Palestinian state."

Should the UN General Assembly approve the current Palestinian proposal, the Palestinians would also be in "fundamental breach" of the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Accord, when the signatories agreed not to attempt to change the status of contested territory before permanent status negotiations were concluded - certainly not before they were even begun.

* * * * *

After the Six-Day War the core Zionist commitment to settling the land of Israel, which had driven state-building efforts since the 1880s, passed from secular to religious Israelis. That transformation surely explains why successive Israeli governments, whether led by Labor or Likud, have either maintained silence - or demonstrated intense hostility - toward Zionist settlers wearing kippot or long skirts.

At best ambivalent - and usually hostile - toward Jews in Judea and Samaria, government officials have resolutely maintained silence about the international guarantees for the "close settlement" of Jews west of the Jordan River.

Joined by a chorus of academic intellectuals, journalists, and cultural luminaries, they have been exceedingly leery of strengthening religious Zionism by authorizing new settlements or enlarging existing ones. The special venom toward settlers displayed by current Defense Minister (and former prime minister) Ehud Barak expresses the deep-rooted hostility of Labor Party and left-wing Zionists toward their despised ideological challengers.

Not all settlers, to be sure, are religious. The majority doubtlessly chose to live in Judea and Samaria because housing prices were lower, and the quality of life better, in their sparkling new communities than where they previously lived.

Perhaps one hundred thousand settlers are religious Zionists who claim the land as Israel's biblical birthright and inheritance. Unlike Tel Avivians, who gaze across the Mediterranean to Los Angeles and the Silicon Valley for their sources of cultural inspiration, these Israelis stand on the bedrock of Jewish history, looking to the past and to sacred texts, not to the West, for inspiration.

Critics from the secular left have been unrelenting in their castigation of settlements. In Lords of the Land (2007), the first comprehensive history of the settlement movement, historian Idith Zertal and Haaretz journalist Akiva Eldar lacerated settlers for their illegal occupation of "Palestinian" land. The "malignancy of occupation," they wrote, "in contravention of international law," has "brought Israel's democracy to the brink of an abyss."

But persistent efforts to undermine the legitimacy of Israeli settlements, wrote international legal expert Julius Stone thirty years ago, have been nothing less than a "subversion of basic international law principles." They still are. Yet the United Nations, with an international constituency that has been relentlessly hostile to Israel ever since it first hallucinated that "Zionism is racism" in 1975, keeps trying.

Catering to international support for Palestinian victimization claims, the International Criminal Court, established by the UN General Assembly in 1998, made Jewish settlement a "war crime." But Israel (like the United States) "unsigned" from the statute of authorization for the Court; furthermore, as international legal scholar Jeremy Rabkin indicates, the Court lacks jurisdiction over "crimes" committed before 2002. By then, virtually all the currently existing Jewish settlements had already been established. That renders any designation of settlements as "war crimes" meaningless ex post facto rhetoric - although not without power to elicit ever more anti-Israel venom.

The question never asked is whether a Palestinian state in the land reserved under international law for "close settlement" by Jews is even legal. The Jewish claim, forged by three thousand years of history in the Land of Israel, including two eras of national sovereignty, reinforced in the modern era by a succession of international legal guarantees, is indisputable.

The Palestinian claim, by contrast, is a contrived recent invention. Palestinians, as Barbara Lerner has written (National Review Online, June 17), "are not a people distinguishable by virtue of their common genes and/or language, religion, culture, history, or form of government."

Devised by Arabs who only recently identified themselves as "Palestinians," it is built on the foundation of perpetual victimization claims, the international determination to delegitimize Israel, and - perhaps most revealing - the pillaging of Jewish and Zionist history.

"Palestine" was so named by the Romans after they crushed the Bar Kochba rebellion in 133 CE. Any ancestors of present-day Palestinians who may have lived in Palestine under Ottoman or British rule were considered by others, and by themselves, to be Arabs. In 1948, without undue protest, they became Jordanians.

Not until the creation of the PLO by Arab states at the Arab League Summit (1964) did they become "Palestinians." It took another decade, which included the stunning victory of Israel in the Six-Day War, before statehood was mentioned on the Palestinian wish list.

The validity of the Palestinian historical claim can be measured by its sources - nearly all of which, revealingly, are Jewish. In a remarkable inversion, a people without an identifiable national identity or history until well into the 20th century has plundered Zionist history to create its own illusory past in a land that was never theirs.

Relying on the Hebrew Bible, Palestinians (like Arabs throughout the Middle East) claim Ishmael, Abraham's son by his servant Hagar, as their founding ancestor. They adopted as their ancient forebears the Canaanites, who, according to the biblical narrative, were displaced by conquering Israelites. (Palestinian history not only invents itself; it anticipates itself.)

Insisting that Jews never had national commonwealths in the Land of Israel many centuries before the birth of Islam, Palestinians reject irrefutable historical and archeological evidence to the contrary.

So, too - like Muslims throughout the Middle East - they resolutely deny that there ever was a Temple in Jerusalem and that the Western Wall has been a Jewish holy site ever since its destruction in 70 CE. Yet triumphant Islam built the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aksa mosque on the Temple Mount precisely because it had been sacred Jewish space.

In Hebron, similarly, Muslim conquerors seized the Cave of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs where Jews had already worshipped at the graves of their biblical ancestors for more than ten centuries. Transforming it into a mosque, Muslims barred Jewish "infidels" from entry for seven hundred years - until the Six-Day War forced open the doors.

Even the flotillas to Gaza, beginning with the notorious Mavi Marmara a year ago, are modeled after the rickety refugee ships that tried to bring desperate Jews, fleeing from Nazi terror and extermination, to Palestine before and after World War II. The most famous of these was the Exodus, with thousands of Holocaust survivors on board, turned away by the British government in 1947. Any resemblance is, of course, purely intentional - and patently absurd.

* * * * *

Might there be an alternative to Palestinian usurpation of the ancient Jewish homeland? Certainly West Bank Palestinians must be guaranteed the right to remain in place, living in their cities and villages and farming their land. They should have the option of citizenship in the Kingdom of Jordan, occupying two-thirds of Mandatory Palestine, where more than half the population is already Palestinian. The distances are not far: from Nablus (biblical Shechem, where Jacob dwelled), the second largest Palestinian city, to Amman it's only 68 miles.

King Abdullah might prefer not to have an even more menacing democratic challenge to his Hashemite minority rule, but that would be a small price to pay for peace.

Jewish settlements, and other land legally owned by Jews in Judea and Samaria, would become part of the Jewish state. On Israeli land there would be no distinctive restrictions on development. A joint Israeli-Palestinian police force could continue to patrol the land between Palestinian and Jewish communities, as has now been done for nearly twenty years.

In Hebron, where the special challenge of a divided city exists, Jews would be free to inhabit Jewish-owned property, which they often cannot (by edict of their own government), and to purchase land and buildings from willing Arab sellers. A continuing Israeli military presence in the Jewish zone of the city, where Arabs also live, would be required indefinitely for the safety of Jewish residents.

In May 1967, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook memorably cried out to his graduates, assembled at the Mercaz HaRav yeshiva in Jerusalem to celebrate Independence Day: "They have divided my land. Where is our Hebron? Have we forgotten it? And where is Shechem? And our Jericho - will we forget them?"

One month later, at the Western Wall, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan promised the victorious nation: "We have returned to all that is holy in our land. We have returned never to be parted from it again."

President Obama, of course, demands otherwise. But his insistence on the 1949 Armistice lines as the framework for negotiation, his determination to propel Palestinian statehood by the end of this year, and his silence on the Palestinian "right of return" (to Israel) easily qualify him as the president most hostile to the Jewish state since 1948 (with the possible exception of Jimmy Carter).

Having quickly turned against a longtime American ally in Egypt, then "leading from behind" in Libya, and now remaining silent while the Assad regime slaughters innocent Syrian civilians, Obama focuses relentlessly on Israel as the primary source of Middle East problems.

The return of Jews to the Land of Israel is what Zionism has always been about. A Palestinian state in the Jewish homeland will undermine it from within.

To find other articles in Think-Israel that address the topic that Mandated Palestine is in an irrevocable trust for the Jewish people, find articles by Shifftan, Grief, Brand, Belman, Kaplan. Other key words are "mandated palestine" and "irrevocable trust". Also see the video entitled "San Remo's Mandate: Israel's 'Magna Carta'" here and a discussion by Jacques Gauthier on the 1967 Lines here.

Jerold S. Auerbach is the author of "Brothers at War: Israel and the Tragedy of the Altalena," published in May by Quid Pro Books. This article was published June 29, 2011 in the Jewish Press and is archived at

http://www.jewishpress.com/pageroute.do/48830/