national review

by Rich Lowry

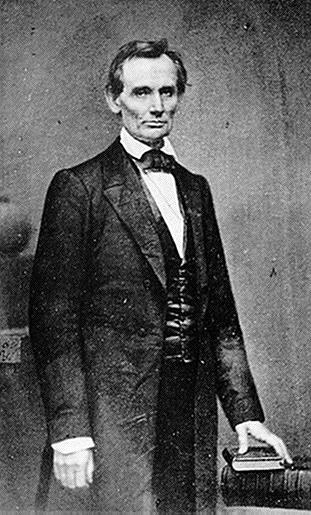

When Abraham Lincoln began his speech at the dedication of the Gettysburg cemetery in 1863 with those words redolent of the King James Bible, “four score and seven years ago,” he referred back to 1776, not 1787.

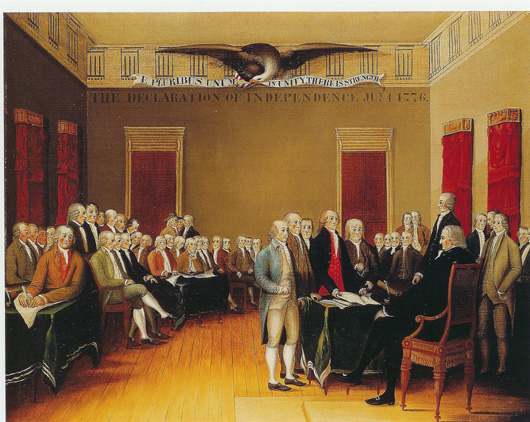

It was the Declaration of Independence, not the Constitution, that animated Lincoln’s project to return mid-19th-century America to our “ancient faith.” For Lincoln, the path of salvation for a country torn by contention over slavery ran through the past: “Our republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust. Let us re-purify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution.”

In the prelude to and during the Civil War — the 150th anniversary of which we mark this year — Lincoln clung to the Declaration as the fundamental statement of the nation’s purpose. The Declaration, according to Lincoln, easily could have enunciated the practical reasons for our split from Britain, and left it at that. No ringing philosophical statements, no invocation of “unalienable rights.”

In the prelude to and during the Civil War — the 150th anniversary of which we mark this year — Lincoln clung to the Declaration as the fundamental statement of the nation’s purpose. The Declaration, according to Lincoln, easily could have enunciated the practical reasons for our split from Britain, and left it at that. No ringing philosophical statements, no invocation of “unalienable rights.”But Thomas Jefferson’s handiwork was meant for the ages. Lincoln praised him for possessing the foresight “to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there, that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.”

Lincoln made precisely this use of the Declaration. Prior to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, overturning the Missouri Compromise and allowing slavery into all the territories if the people wanted it, he referred to the Declaration in public only twice. In the ensuing crisis, it became a staple of his rhetoric.

Lincoln’s historic debates with Illinois senator Stephen Douglas, the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, were at bottom an argument about the Declaration. Under his doctrine of “popular sovereignty,” Douglas wanted to allow the extension of slavery in blatant disregard of the belief that “all men are created equal.”

Douglas denied that the Declaration had universal meaning. The Founders merely meant to say that as British subjects in North America we were equal to British subjects in Britain. What appeared to be a ringing statement of eternal truth was in reality a dubious assertion that all men are British.

Worse, Douglas and his ilk — Chief Justice Roger Taney and all the apologists for the slave power — also fell back on the argument that blacks weren’t men. If so, Lincoln wondered, why did the country permit half a million blacks their freedom? “How comes this vast amount of property to be running about without owners? We do not see free horses or free cattle running at large.”

The popular sovereignty of Douglas depended, ultimately, on believing the Declaration a lie. One of the reasons Lincoln said he hated slavery was “that it forces really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty — criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.”

This view threatened the foundation of freedom. “A free people cannot disagree, or agree to disagree, on the relative merits of freedom and despotism,” the great Lincoln scholar Harry Jaffa writes. “If the majority favors despotism, it is no longer a free people, whether the form of government has already changed or not.”

Lincoln lost the 1858 Senate election, of course, but he succeeded ultimately in vindicating the Declaration. It should remain today what Lincoln fought to establish it as: the timeless object for our national aspiration. “They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society,” Lincoln said of the Founders, “which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”

— Rich Lowry is editor of National Review. He can be reached via e-mail, comments.lowry@nationalreview.com. © 2011 by King Features Syndicate.