In August, two pieces of news about Iran’s nuclear ambitions were revealed almost simultaneously. The first was that Iran had fired up its first nuclear reactor. The second, delivered in an ostentatious leak to the New York Times, was that the Obama administration had determined that Iran was at least a year away from a “dash” necessary to complete a working nuclear weapon—and that the White House had succeeded in convincing Israel that there was no imminent threat.

The reactor news suggested the seriousness with which Iran was pursuing its nuclear ambitions. The “dash” story suggested the degree to which the United States was determined not to view the working Iranian reactor as a crisis requiring immediate and determined attention. Despite the Times article’s sense of certainty that Israel’s leaders had achieved a state of sangfroid about the approaching danger, the August news unquestionably accelerated the sense inside the Jewish state that action against Iran would be unavoidable, and that Israelis would not be delivered from the overwhelming burden of taking action themselves.

It is critical to explain precisely the danger posed to Israel by a decision to strike Iran—without question the most difficult, complex, and perilous military mission in the state’s 62-year history. One need only recall the universal condemnation of Israel’s 1981 attack on the Iraqi reactor at Osirak and the more muted, but still

It is critical to explain precisely the danger posed to Israel by a decision to strike Iran—without question the most difficult, complex, and perilous military mission in the state’s 62-year history. One need only recall the universal condemnation of Israel’s 1981 attack on the Iraqi reactor at Osirak and the more muted, but still palpable, criticism of Israel’s destruction of Syria’s nuclear-reactor-in-progress in 2007 to imagine the scope of the worldwide outrage that would follow Israeli attacks on Teheran’s nuclear facilities and infrastructure—likely causing in the process far greater civilian casualties than did either of those previous missions. The claim that Israel had to act to prevent a nuclear attack on its cities would be quickly dismissed: “With an appreciable nuclear arsenal of its own, Israel has second-strike

capabilities that would almost certainly have prevented Teheran from attacking first,” it will be said. And, many would insist, why didn’t repeated American assurances that the U.S. would resoundingly punish any attack on Israel stay the Jewish state’s hand? What possible justification could there be for Israel’s precipitous military action?

What must be understood is that the threat to Israel is not that Iran will one day use the bomb. No, Iran merely needs to possess the bomb to undermine the central purpose of Israel’s existence—and in so doing, to reverse the dramatic change in the existential condition of the Jews that 62 years of Jewish sovereignty has wrought. The mere possession of a nuclear weapon by Iran would instantly restore Jews to the status quo ante before Jewish sovereignty, to a condition in which their futures would depend primarily on the choices their enemies—and not Jews themselves—make.

What must be understood is that the threat to Israel is not that Iran will one day use the bomb. No, Iran merely needs to possess the bomb to undermine the central purpose of Israel’s existence—and in so doing, to reverse the dramatic change in the existential condition of the Jews that 62 years of Jewish sovereignty has wrought. The mere possession of a nuclear weapon by Iran would instantly restore Jews to the status quo ante before Jewish sovereignty, to a condition in which their futures would depend primarily on the choices their enemies—and not Jews themselves—make._____________

For hundreds of years, Jewish life in Europe was a matter of either hoped-for toleration or a struggle to survive against the periodic outpourings of violent Jew-hatred. During the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290, the Spanish Inquisition some 200 years later, the state-encouraged pogroms that would sow terror in Jewish communities across the continent intermittently in the centuries that followed, and the culmination of all this hatred in the Nazi death machine, there was little Jews could do in the face of the onslaught. Oh, there were episodic (and largely ineffective) pockets of resistance, and powerful liturgical, poetic, exegetical, and literary traditions emerged from the tragedies; but the Jewish experience inEurope was fundamentally one of defenselessness. What happened to the Jews was whatever theirenemies determined should happen to them.

The creation of the State of Israel fundamentally changed not only that reality but also the self-perception that accompanied it. It was in pre-statehood Palestine, after centuries of utter passivity, that the Jews finally took up arms to defend themselves. Unlike the 1943 uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto, one of history’s most moving acts of hopeless defiance, the newfound Jewish willingness to fight was not destined to defeat, and the Jewish willingness to die was not merely symbolic. Against

what seemed to be insurmountable odds, ragtag warriors—outmatched and outgunned—defeated the numerous armies that most people expected would drive the Jews back into the sea and actually expanded the borders of their newly created state. The creation and survival of the Jewish state in the late 1940s ended a millennium of abject Jewish vulnerability and brought to an astonishing close a long and anguished history in which Jews were assigned the role of victim-on-call.

Many people are put off by the Israeli national affect, which they take to be a mix of arrogance and bravado. This is a misperception of an attitude that is born, in truth, out of collective relief: We Jews no longer live—and die—at the whim of others. That sense of security would evaporate the minute Iran had the weapon it seeks. Even if Israel does possess a second-strike capability, and even if the U.S. could be counted on to punish a nuclear attack on the Jewish state, the existential condition of the Jews would still have reverted to that experienced in pre-state Europe. It would mean that Jews by the tens of thousands could die because someone else determined that it was time for them to do so. No action that Israel could take in response would change that fundamental reality.

Many people are put off by the Israeli national affect, which they take to be a mix of arrogance and bravado. This is a misperception of an attitude that is born, in truth, out of collective relief: We Jews no longer live—and die—at the whim of others. That sense of security would evaporate the minute Iran had the weapon it seeks. Even if Israel does possess a second-strike capability, and even if the U.S. could be counted on to punish a nuclear attack on the Jewish state, the existential condition of the Jews would still have reverted to that experienced in pre-state Europe. It would mean that Jews by the tens of thousands could die because someone else determined that it was time for them to do so. No action that Israel could take in response would change that fundamental reality.The dramatic change in Jewish self-perception that Israel has wrought can perhaps be best appreciated by recalling two photographs—each, in its own time, the iconic representation of what it meant to be a Jew. The first, taken in the Warsaw Ghetto, depicts a terrified young boy, his arms raised helplessly in the air, as a Nazi

points a submachine gun in his direction. This little boy, a victim in every way, is dressed in his finest but seems likely to die. He is alone; no adults have come to his aid, and even if they chose to, of course, there would be nothing they could do in the face of the armed Nazis standing just feet away. To be a Jew is to be a victim.

points a submachine gun in his direction. This little boy, a victim in every way, is dressed in his finest but seems likely to die. He is alone; no adults have come to his aid, and even if they chose to, of course, there would be nothing they could do in the face of the armed Nazis standing just feet away. To be a Jew is to be a victim.Flash-forward to June 1967, when the Israeli photographer David Rubinger photographed three paratroopers at the Western Wall shortly after they had captured it from Jordan during the Six-Day War. It was the virtual undoing of the condition reflected in the Warsaw Ghetto photograph. The boy in the photograph is alone; these three men are surrounded by comrades. The boy is pure victim; the Israeli soldiers are victors. The gun in the former photograph belongs to the Nazi; there are no weapons in the 1967 picture, but had there been, they would have belonged to the Jews. The boy in the Warsaw Ghetto seems certain to die; the victory these soldiers had just wrought would breathe new life into the Jewish state, inspiring Soviet Jews (who almost immediately demanded permission to emigrate) and American Jews (who took a sudden great pride in the Jewish state and expressed it more openly and unabashedly than at any time before) to new heights of Zionism.

Interestingly, the paratroopers in this photograph have their heads uncovered, and they face away from the Wall, not toward it, as would be the case were they praying. There is one combat helmet, and though it is visible, it has been doffed. Rubinger’s is neither a religious nor a military image. It is, instead, the image of the “new Jew” that Israel had created, the Jew who could shape his or her own destiny rather than waiting for it to be shaped by others.

Interestingly, the paratroopers in this photograph have their heads uncovered, and they face away from the Wall, not toward it, as would be the case were they praying. There is one combat helmet, and though it is visible, it has been doffed. Rubinger’s is neither a religious nor a military image. It is, instead, the image of the “new Jew” that Israel had created, the Jew who could shape his or her own destiny rather than waiting for it to be shaped by others.This notion of Jews as the masters of their own destiny, as defenders of their own lives, is the deepest core of the Jewish state. In the space of eight days each spring, Israel commemorates Holocaust Memorial Day, then Memorial Day for Fallen Soldiers, then Independence Day. It is a period of profound national consciousness, punctuated with public rituals neither political nor religious. Each and every year, the speech delivered by the head of state, Israel’s president, on Holocaust Memorial Day boils down to one simple claim: had Israel existed then, this would not have happened.

On the evening of Holocaust Memorial Day and then, a week later, on both the morning and evening of Memorial Day for Fallen Soldiers, the nation freezes in place as a siren is sounded—cars come to a halt on highways, their drivers stand at attention just outside their vehicles, and people on sidewalks become immobile. All that can be heard is the harrowing groan of the air-raid siren as the nation mourns its thousands upon thousands of sons and daughters, soldiers who died in defense of the country. Coming as it does a week after Holocaust Memorial Day, the calendrical point requires no emphasis. Better we should die on battlefields, armed and defending our homeland, than be shepherded into camps in someone else’s country, utterly defenseless. For better and for worse—better because it’s true, and worse because the society established on this basis is of necessity extraordinarily complex and fraught—that is the point of the Jewish state.

Periodically, as my 21-year-old son heads back to the army at the crack of dawn on a Sunday morning after a weekend at home, I’ll kid with him as he’s walking out the door with all his gear, mimicking conversations we might have had when he was a teenager. I’ll ask, in a falsely harsh tone, “Just where do you think you’re going at this time of the day?” To which he’ll smile and say, “To defend the homeland.”

It has become ritualized family banter, but only because the first time my son responded that way, he did so without thinking, without humor, and without irony. It was, in point of fact, exactly where he was headed. He was going to defend the homeland. The thousands upon thousands of young Israelis who serve their country this way, some of whom volunteer for roles more daunting than could possibly be described, do what they do, day after day and year after year, because they believe themselves capable of defending the homeland. On land, in the air, and at sea, they have proved decade after decade, war after war, that periodic failings notwithstanding, they can keep the country safe. They leave their homes behind, and risk life and limb to ensure the safety of their parents, their grandparents, their siblings, and often their children.

And all this—these national rituals and this still pervasive willingness to serve—would lose all meaning were Jews returned to the status of European victims-in-waiting. Which is precisely what an Iranian nuclear weapon would do.

My son and his cohort, then and now, could stop the Soviet fighter aircraft the Egyptians used in 1967 and the Soviet tanks the Syrians used in 1973; they could act against those who fire Qassam rockets from Gaza at Sderot and (with increasing accuracy) neighborhoods in Ashkelon, and they could move into West Bank towns and build the fence that would bring an end to the Palestinian suicide bombers. But there is nothing these soldiers could do to stop an Iranian nuke on its way to Israel. There would be no time to stop it. Instead, Israel’s military deterrent against the greatest threat to its existence and the continued existence of the Jewish people would be intellectual, theoretical, a matter of international nerve and round-robin negotiations, the proffering of carrots, the hoped-for intervention of the “international community” to keep Iran sane. Israel’s safety and future would no longer rest in the hands of its people, its soldiers, its reservists, its young and its old. It would no longer be my son defending the homeland but something else—a “second-strike capability.” A worldwide attitude. An American threat that might well be hollow would be all we could rely on.

Even more chilling, this would happen against the backdrop of a country that is both emotionally and ideologically exhausted.

Yes, Israel’s economy is chugging along impressively, the army has been reconstituted since the Second Lebanon War, Israel still wins more than its share of Nobel Prizes, and the cafés are filled with people socializing and leading what looks like the good European life. Yet beneath this veneer, Israel is bone-weary. On its campuses, increasing numbers of faculty members espouse the notion that Zionism is colonialism. Draft evasion is at an all-time high. The international delegitimization of Israel haunts day-to-day life.

Perhaps most important, today’s Israeli parents are the first generation to send their children to war unable to console themselves with the notion that theirs will be the last generation of children that will have to fight. Few Israelis believe that anymore. Palestinian recalcitrance is much more deeply rooted than many Israelis had hoped. And even if Fatah eventually makes a deal with Israel, Hezbollah, Hamas, and Iran have made it clear that they never will. So the conflict will linger on, and today’s young soldiers head off to battle knowing that if they survive, they will one day send their own children to do the same thing.

One can sustain a commitment to this sort of existence only with the certainty that it makes an enormous difference. Until now, it has, and Israelis have known that. But after Iran has a nuclear capability that rests in the hands of evil men who believe that the Jewish state is a disease in its midst and that Judaism itself is a foul doctrine—in what way will the existential Jewish condition be all that different from what it was in Central Europe in the early 1930s?

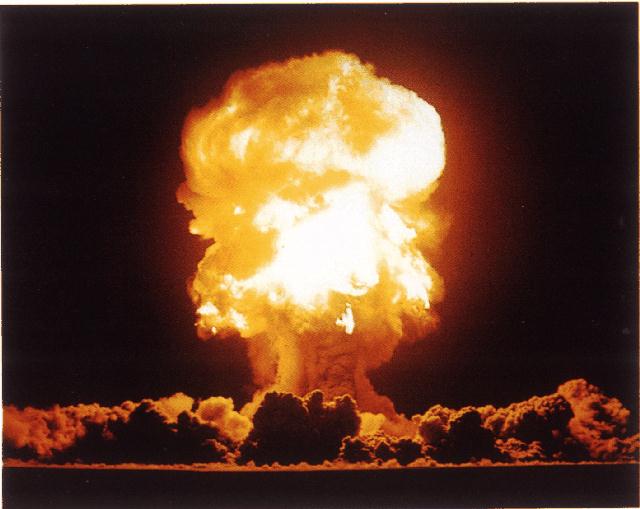

To be sure, Israel boasts a flourishing Jewish culture, a renewed Hebrew language, and an impressive array of Jewish accomplishments that could not have happened without the state. But all that, impressive as it is, is insufficient. For the first commitment of Zionism has been to provide safety to Jews. So far, it has more or less succeeded. But the minute that Iran possesses its long-sought nuclear weapon, Zion becomes not a haven for the Jews but a potential deathtrap. Six million Jews (an ironic number if there ever was one) will again be in the crosshairs. And if that happens, Israel will have lost its purpose.

Without purpose, Israelis will not remain in Israel. The allures of Boston and Silicon Valley, where intellectual and financial opportunity await without the burdens of war and the shadow of extinction, will be too difficult to resist. Those who now stay in Israel do so, in large measure, because they sense they are part of a historic transformation of the Jewish condition. Absent that awareness, however, the most mobile of Israel’s citizens—who also happen to be those whom the state most desperately needs—will be the ones who abandon it.

In this way, Iran could end the Jewish state without ever pressing the button.

_____________

All of Israel’s senior politicians understand Israel’s historic responsibility to and for the Jewish people. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s father was secretary to Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of the hard-line Revisionist Zionist movement. The head of the Kadimah Party, Tzipi Livni, was born to parents who had been members of the Irgun underground, which fought the British and the Arabs in the years before the state’s founding. All four of Labor Party leader Ehud Barak’s grandparents were murdered in Europe. Israel remains a nation whose leadership is possessed of profound historical consciousness.

For these reasons alone, it seems highly unlikely that any of those three leaders would willingly permit Iran to go nuclear. It is therefore critical that the world understand what is at stake for Israel. Should Israel strike first, the international community will need to understand what motivated that strike. Indeed, a true grasp of the stakes for Israel might be the only thing that could avert the need for an Israeli strike.

If Barack Obama could come to understand in precisely what way this is a matter that goes to the heart of Israel’s very existence—and, one might add, the existence of the Jewish people as a people, because we cannot survive a second act of mass murder in a single century—his administration might recognize the profound nature of the present moment and history’s call to this president to do what must be done.

© 2010 Commentary Inc.